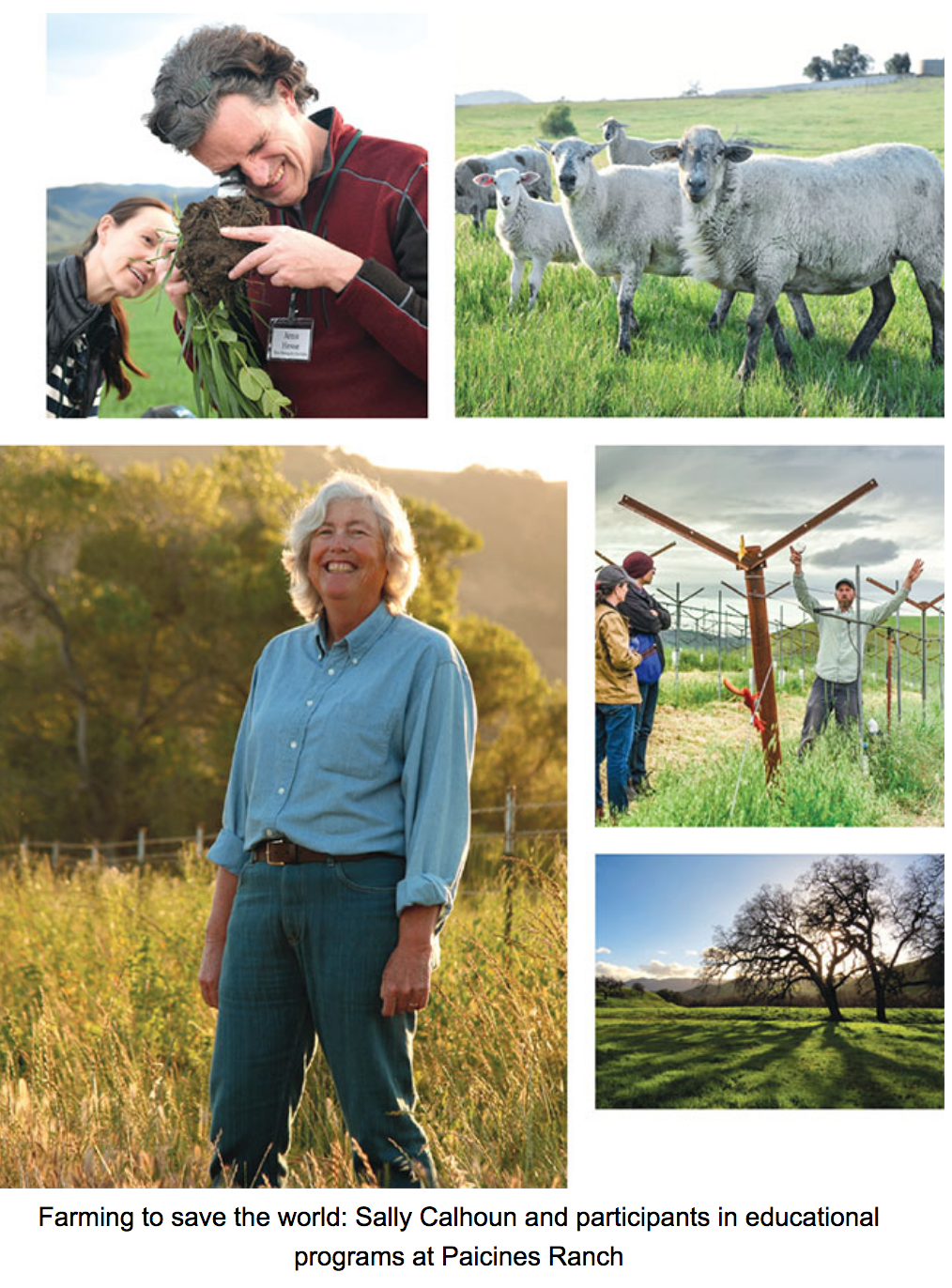

ON THE FARM: REVOLUTIONARY RANCHER

A former engineer takes on climate change with regenerative agriculture

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALICIA ARCIDIACONO AND ELAINE PATARINI

Sallie Calhoun couldn’t have been more surprised when her husband got the wild idea of buying the huge and historic Paicines Ranch south of Hollister 17 years ago.

The land had been slated for a resort hotel, golf course and 4,500- unit housing development, but San Benito County wanted the developers to provide a four-lane highway to serve all the new commuters, and that just wasn’t going to happen. So Calhoun and her husband Matt Christiano purchased the land and settled in, curious about their future.

Calhoun’s father left his family’s farm in the rural South to become an engineer in the 1950s. As much as she loved summer visits to the farm, she loved math and science more, so she followed in her father’s footsteps and became an electrical engineer just as Silicon Valley was emerging.

In her spare time, she liked to garden in her Los Gatos backyard and took up the environmental cause of restoring native California perennial grasses in her raised beds. Little did she know she would soon have 7,600 acres to play in, as an unsolicited buyout of their engineering firm allowed the couple to become innovative ranchers and philanthropists at an age when all their cylinders were still firing.

Paicines Ranch was started in the mid-1800s as a dairy. It was also once part of Mirassou Winery’s vineyards and, more recently, was sectioned off and leased to a cattle rancher and an organic vegetable farmer. At first, the challenges of managing a property in a region that averages just 10 inches of rain per year seemed daunting. Looking for a way to rebuild topsoil with native grasses, Calhoun found the ecologist Allan Savory—who believes grazing can reverse climate change and desertification—and she joined the board of his Holistic Management International in arid New Mexico.

“I vividly remember the moment when I got the idea that you might be able to sequester carbon and mitigate climate change,” she says. “I was at a Holistic Management board meeting in Albuquerque, and as a side conversation somebody was talking about paying ranchers to sequester carbon. It had never, ever occurred to me that you could suck carbon out of the air and put it back in the soil. That to me was just the absolute coolest thing.

“The whole weekend that’s all I thought about. What if you could regenerate grasslands and address climate change? How amazing is that? And how is it that the whole world isn’t talking about doing this? And that’s where I still am over 10 years later,” she adds.

Over the years, Paicines Ranch has steadily built its reputation as the go-to learning center for regenerative agriculture in central California, but it hasn’t been easy. In 2016, education director Elaine Patarini recalls she had to beg people to attend a workshop with soil ecologist Dr. Christine Jones, who flew all the way from Australia to address a ragtag crew of early adopters.

“It would be good to be able to say ‘the earth will be fine,’ but we don’t really know that right now.”

But this past December, 100 eager participants maxed out the ranch’s event center to learn from Jones, suggesting that the tipping point toward a regenerative agriculture movement is at hand. In January, Calhoun hosted EcoFarm’s sold-out pre-conference workshop on the same topic. The growing local interest is part of a nationwide movement pioneered by no-till visionaries in the Midwest and further east who have learned to manage rangelands with herds of livestock that imitate the behavior of native buffalo, grouping together to avoid predators, munching and fertilizing as they are herded along, giving plants time to recover and grow.

SAVE THE PLANET

As we all learned in grade school, plants grow through the alchemy of photosynthesis. This natural activity uses sunlight to make carbohydrates by combining water and carbon dioxide from the air, which are then fed down through the plant into the soil to beneficial bacteria and fungi below. It turns out this wildly underappreciated process is one of the keys to balancing the greenhouse gases we spew into the air. As plants turn light into life, they feed CO2 into the soil through their roots. It’s our job to keep it there.

Wait…what? You mean the more plants we grow and allow to live undisturbed in the ground, the more carbon we capture? That’s the theory. And Calhoun is a rancher with enough curiosity and acreage to be taken seriously. She’s also an incredibly welcoming host who has attracted researchers, teachers and ranchers from across the U.S. and around the world, sometimes to stay for a few days in comfortable quarters that double as wedding venue suites on summer weekends.

“I feel this terrible sense of urgency, and I wish I didn’t,” Calhoun says. “If we weren’t in the middle of climate change with maybe 60 years of topsoil left, it might actually be more fun and less stressful. It would be good to be able to say ‘the earth will be fine,’ but we don’t really know that right now.”

What Jones teaches is the benefit of the liquid carbon pathway in green plants, which she describes as a “soil microbial carbon pump.” Photos from a scanning electron microscope show that mycorrhizal fungi actually pierce the roots in the soil. What scientists are excited to discover is how this process makes nutrients available to plants. Pastured animals encourage this activity because they eat only the tops of plants, stimulating the roots to seek sustenance from the soil to regrow the tops. Pastures allowed to recover through managed grazing— moving animals before they denude the field—are part of a living ecosystem.

Our inability to see the beauty of photosynthesis and our inadvertent willingness to destroy soil communities are becoming clear. But if tilling is so destructive, what are farmers going to do? And why did it take Western civilization 5,000 years to figure this out? Many of the people who care deeply about these concerns eventually find their way to Paicines Ranch, where Calhoun is a skilled matchmaker.

“I think our work is connecting a lot of circles of people,” Calhoun says. “Our strategy is to continue to be a center for education and demonstration and really bring people together. The whole thing changes when people develop relationships with each other and with the earth. We think of ourselves as inoculants—trying to create a mycelium. So we’re trying to create the kind of fungus that connects us all. And once we’re all connected, we can do anything.”

In March Paicines hosted its first-ever Learning Journey event for investors and funders through the #NoRegretsInitiative.

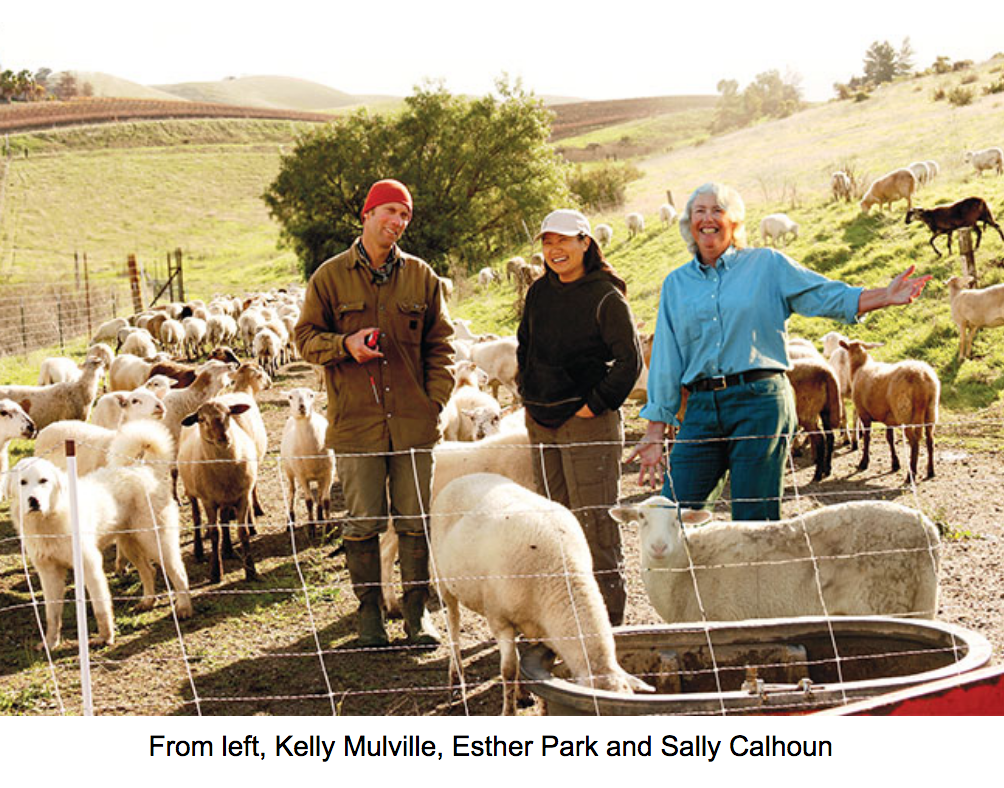

The goal is for people investing and making grants in sustainable agriculture to ask themselves, “How do I understand enough about this to be intelligent in my work and to really be helpful?” Included on the team are Nikki Silvestri and Esther Park, innovators in sustainability investing.

“Nikki helped me recognize the value of sharing the importance of soil health with my peers in social finance. Esther is CEO of Cienega Capital, an investment firm I founded for soil health, regenerative agricultural practices and local food systems,” Calhoun says.

In April, the #NoRegretsInitiative convened its third annual Lead with Land meeting. These relatively small gatherings of 16 major landowners provide hands-on relationship building with the regenerative ag community and breakthrough thinking on decision-making around the various possible meanings of return on investment. Not every return is going to be financial.

Among the guiding principles developed by Lead with Land is: “Leaving the design of a new food and land system to existing bureaucracies, power structures and conventional land management techniques will not lead to restoration. Intervention is needed.”

TAKING ROOT

A few years ago Calhoun was able to hire the regenerative ag hero Kelly Mulville as ranch manager at Paicines. Mulville was so inspired by the holistic management message that he rode his bike at age 18 from West Texas to Albuquerque to meet Allan Savory and went on to become one of the first in the nation to put planned grazing into practice. He was excited to show me a tall type of vineyard trellis he designed so grapevines can be suckered by sheep. Suckering, or pruning back unwanted growth, is a costly farm job turned over to the ruminants, which provide fertilizer as a bonus in Mulville’s realm. The sheep won’t be able to reach the grapes or photosynthesizing leaves high up on the trellis, but they will be able to trim the ends of grapevines that get too long.

Two years were spent preparing the soil in the vineyard. This involved tall cover crops grazed by sheep in a managed rotation, using electric fencing, the roots left in the ground before the grape trellises went up.

“Our intention is never to till again, to always keep the ground covered and to graze as a regular part of maintenance,” Calhoun says. “Kelly says that in many California vineyards you can have an average of 25 tractor passes up and down each row each year. So you have all this compaction and you have bare ground.”

As organic matter improves, so does the water-holding capacity of soil, something she feels should speak volumes to Californians, as using undisturbed vegetation to keep soils moist implies water savings. Fields of row crops on the ranch used to be leased to a local organic farmer, but Calhoun wanted to go beyond organic, and decided to farm it herself.

“Though our crop ground is certified organic, it was being cultivated in a way that is extractive, destroying soil health and releasing carbon into the atmosphere,” in particular, subjecting the land to frequent tilling, she says. “We decided we could no longer watch what was happening in that kind of organic veggie production. So they are now gone and we’re in the process of becoming farmers, which I said I would never do.

“We have a lot of skin in the game. We gave up that rent check. It’s a big thing to give up a rent check that falls on your desk every month, to do this experiment,” she says with a wry smile.

The work at Paicines Ranch is beginning to influence farmers in the Monterey Bay region. Phil Foster of Pinnacle Organic, an early user of many regenerative farming practices near San Juan Bautista, attended both of Jones’ sessions and displayed his experimental plots for the EcoFarm bus tour in January. Foster will never use animals in the fields due to food safety laws and his focus on fresh organic vegetables. However, he has long believed strongly in compost and made his own.

“With 25 years of compost applications and extensive cover cropping to improve soil organic carbon and soil biology with good results, we are incorporating practices to significantly reduce tillage in our vegetable production for increased improvements in soil quality,” Foster says. “Our goal is to reduce tillage by 50% or more for the next five years to see if we can get measurable increases in soil organic carbon.”

When asked about succession, Calhoun says her children are not interested in becoming ranchers. “We hope that people coming here will start to feel like it is ‘Their Ranch’ and we can hold on to it as a functioning nonprofit.” Many ranch tours and activities are available each year; descriptions and dates can be found on the Paicines Ranch website, paicinesranch.com.

The real legacy Calhoun hopes to leave is that she did all she could to address climate change in our precarious era.

WHAT IS REGENERATIVE ORGANIC CERTIFICATION?

Some people don’t think the USDA Organic certification goes far enough. Others see recent moves as weakening the organic standard— particularly a decision last year to continue allowing hydroponically grown produce to be labeled organic and a decision in early 2018 to withdraw new and widely praised animal welfare rules.

A new Regenerative Organic Certification that builds on the organic movement is being launched by the Rodale Institute. Backed by Patagonia, Demeter USA, Dr. Bronner’s and a variety of other organic brands, the new certification is built on these three pillars:

Soil Health: minimal tillage, cover crops, crop rotation, rotational grazing, no synthetic inputs, no GMOs or gene editing, promotion of biodiversity, building soil organic matter and no soil-less systems.

Animal Welfare: five freedoms, grass fed/pasture raised, no concentrated animal feeding operations, suitable shelter and limited animal transport.

Social Fairness: fair payments for farmers, living wages, no forced labor, democratic organizations, long-term commitments, transparency and accountability, good working conditions, capacity building and freedom of association.

Meantime a second group called the Real Organic Project has emerged, offering an alternative, add-on label to USDA-certified organic products that would guarantee that produce is grown in soil and livestock is raised in pasture-based systems.

Still, both proposals have raised concerns among people who fear that too many labels will confuse consumers.

For a deeper dive into regenerative agriculture, look for these resources:

Further Reading

David Montgomery, three books: Growing a Revolution (2017), Dirt (2007), andThe Hidden Half of Nature (2016) with co-author Anne Biklé.

Kristin Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us (2014)

Paul Hawken, Drawdown (2017)

The New York Times Magazine, “Can Dirt Save The Earth?” April 15, 2018, Moises Velasquez-Manoff www.nytimes.com/2018/04/18/magazine/dirt-save-earth-carbon-farming-climate-change.html

Dr. Christine Jones, “SOS: Save Our Soils,” March 2015 www.amazingcarbon.com/PDF/Jones_ACRES_USA%20%28March2015%29.pdf

Video

The Soil Story a brief impactful video by Kiss the Ground www.youtube.com/watch?v=nvAoZ14cP7Q

Classes